Space news is back! We decided to move to a monthly format for now while yours truly is very busy playing with Moon rocks, meterorites and cool shit like that. The cover photo is a lunar basalt in thin section I took through the microscope last week. Jealous much? Kind of looks seasonal too! So lets see what fun stuff has been going on.

Pluto’s Pot of Gold

Having traveled from the New Horizons spacecraft over 5.5 billion kilometers (five hours, eight minutes at light speed), the final item – a segment of a Pluto-Charon observation sequence taken by the Ralph/LEISA imager – arrived at mission operations at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, at 5:48 a.m. EDT on Oct. 25. The downlink came via NASA’s Deep Space Network station in Canberra, Australia. It was the last of the 50-plus total gigabits of Pluto system data transmitted to Earth by New Horizons over the past 15 months.

“The Pluto system data that New Horizons collected has amazed us over and over again with the beauty and complexity of Pluto and its system of moons,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “There’s a great deal of work ahead for us to understand the 400-plus scientific observations that have all been sent to Earth. And that’s exactly what we’re going to do—after all, who knows when the next data from a spacecraft visiting Pluto will be sent?”

Because it had only one shot at its target, New Horizons was designed to gather as much data as it could, as quickly as it could – taking about 100 times more data on close approach to Pluto and its moons than it could have sent home before flying onward. The spacecraft was programmed to send select, high-priority datasets home in the days just before and after close approach, and began returning the vast amount of remaining stored data in September 2015.

“We have our pot of gold,” said Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman, of APL.

In the meantime, the mission scienctists have been pondering the mysteries of Pluto’s mysterious heart and its origin. One school of thought suggests that an impact may have created it, another hints at a possible subsurface liquid ocean. One recent paper, by lead author Francis Nimmo of the University of California Santa Cruz, and New Horizons colleagues, modeled how Sputnik Planitia could have formed if its basin was produced by an impact, such as the one that created Charon. In this scenario the basin formed and migrated to its present location after Pluto slowed its rotation. “The migration happens because of extra mass beneath Sputnik Planitia,” Nimmo said. “An impact will excavate ice at the surface, letting any water underneath it approach closer to the surface. Because water is denser than ice, it provides a source of extra mass to help drive Sputnik’s migration.”

An ocean beneath the surface can survive for billions of years because of heat produced by radioactive decay in Pluto’s rocky interior, he said, adding that the slow refreezing of an ocean can also explain the network of fractures seen on Pluto’s surface.

“Sputnik Planitia is one of Pluto’s crown jewels, and understanding its origin is a puzzle,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. “These new papers take us a step closer to unraveling this mystery. Whatever caused Sputnik to form, nothing like it exists anywhere else in the solar system. Work to understand it will continue, but whatever that origin is, one thing is for certain—the exploration of Pluto has created new puzzles for 21st century planetary science.”

So, a subsurface water ocean? Could life possibly be able to survive so far out in the Solar system? Worth a thought!

Staying on the subject of water..

Martian Ice Deposit as large as Lake Superior

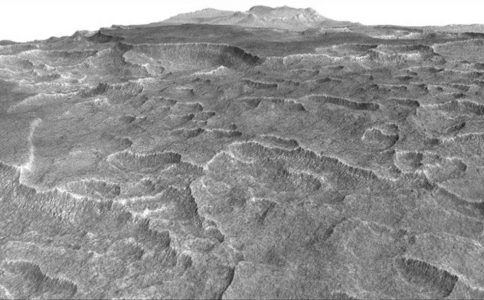

Frozen beneath a region of cracked and pitted plains on Mars lies about as much water as what’s in Lake Superior, largest of the Great Lakes, researchers using NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have determined.

Scientists examined part of Mars’ Utopia Planitia region, in the mid-northern latitudes, with the orbiter’s ground-penetrating Shallow Radar (SHARAD) instrument. Analyses of data from more than 600 overhead passes with the onboard radar instrument reveal a deposit more extensive in area than the state of New Mexico. The deposit ranges in thickness from about 80 meters to about 170 meters, with a composition that’s 50 to 85 percent water ice, mixed with dust or larger rocky particles.

At the latitude of this deposit — about halfway from the equator to the pole — water ice cannot persist on the surface of Mars today. It sublimes into water vapor in the planet’s thin, dry atmosphere. The Utopia deposit is shielded from the atmosphere by a soil covering estimated to be about 1 to 10 meter thick.

“This deposit probably formed as snowfall accumulating into an ice sheet mixed with dust during a period in Mars history when the planet’s axis was more tilted than it is today,” said Cassie Stuurman of the Institute for Geophysics at the University of Texas, Austin. She is the lead author of a report in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Mars today, with an axial tilt of 25 degrees, accumulates large amounts of water ice at the poles. In cycles lasting about 120,000 years, the tilt varies to nearly twice that much, heating the poles and driving ice to middle latitudes. Climate modeling and previous findings of buried, mid-latitude ice indicate that frozen water accumulates away from the poles during high-tilt periods.

Martian Water as a Future Resource

The name Utopia Planitia translates loosely as the “plains of paradise.” The newly surveyed ice deposit spans latitudes from 39 to 49 degrees within the plains. It represents less than one percent of all known water ice on Mars, but it more than doubles the volume of thick, buried ice sheets known in the northern plains. Ice deposits close to the surface are being considered as a resource for astronauts.

“This deposit is probably more accessible than most water ice on Mars, because it is at a relatively low latitude and it lies in a flat, smooth area where landing a spacecraft would be easier than at some of the other areas with buried ice,” said Jack Holt of the University of Texas, a co-author of the Utopia paper who is a SHARAD co-investigator and has previously used radar to study Martian ice in buried glaciers and the polar caps.

The Utopian water is all frozen now. If there were a melted layer — which would be significant for the possibility of life on Mars — it would have been evident in the radar scans. However, some melting can’t be ruled out during different climate conditions when the planet’s axis was more tilted. “Where water ice has been around for a long time, we just don’t know whether there could have been enough liquid water at some point for supporting microbial life,” Holt said.

In the Canadian Arctic, similar landforms are indicative of ground ice, Osinski noted, “but there was an outstanding question as to whether any ice was still present at the Martian Utopia or whether it had been lost over the millions of years since the formation of these polygons and depressions.”

The large volume of ice detected with SHARAD advances understanding about Mars’ history and identifies a possible resource for future use.

“It’s important to expand what we know about the distribution and quantity of Martian water,” said Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Deputy Project Scientist Leslie Tamppari, of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “We know early Mars had enough liquid water on the surface for rivers and lakes. Where did it go? Much of it left the planet from the top of the atmosphere. Other missions have been examining that process. But there’s also a large quantity that is now underground ice, and we want to keep learning more about that.”

Joe Levy of the University of Texas, a co-author of the new study, said, “The ice deposits in Utopia Planitia aren’t just an exploration resource, they’re also one of the most accessible climate change records on Mars. We don’t understand fully why ice has built up in some areas of the Martian surface and not in others. Sampling and using this ice with a future mission could help keep astronauts alive, while also helping them unlock the secrets of Martian ice ages.”

Cassini High-Flying to its Swansong

Nearly 20 years after its launch in 2007, the aging craft is being readied for a series of deep dives through Saturn’s rings. The craft has made some dramatic discoveries such as the subsurface ocean on Enceladus and methane lakes and seas on Titan. With the craft now running out of fuel, the mission team intends to get as much scientific data as they can.

“We’re calling this phase of the mission Cassini’s Ring-Grazing Orbits, because we’ll be skimming past the outer edge of the rings,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “In addition, we have two instruments that can sample particles and gases as we cross the ringplane, so in a sense Cassini is also ‘grazing’ on the rings.”

On many of these passes, Cassini’s instruments will attempt to directly sample ring particles and molecules of faint gases that are found close to the rings. During the first two orbits, the spacecraft will pass directly through an extremely faint ring produced by tiny meteors striking the two small moons Janus and Epimetheus. Ring crossings in March and April will send the spacecraft through the dusty outer reaches of the F ring.

“Even though we’re flying closer to the F ring than we ever have, we’ll still be more than 7,800 kilometers distant. There’s very little concern over dust hazard at that range,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL.

Now in its final year of operations, on Nov. 30, 2016, NASA’s Cassini mission began a daring set of ring-grazing orbits, skimming past the outside edge of Saturn’s main rings. Cassini will fly closer to Saturn’s rings than it has since its 2004 arrival. It will begin the closest study of the rings and offer unprecedented views of moons that orbit near them. Even more dramatic orbits ahead will bring Cassini closer to Saturn than any spacecraft has dared to go before.

A joint endeavour by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Italian Space Agency, and originally engaged on a four-year study of the Saturn system, the Cassini-Huygens mission was extended in 2008 and again in 2010. But although the end is nigh, it is hoped Cassini will keep giving, right up to the last.