Enceladus is the sixth largest moon of Saturn, with a diameter of about 500km. At one seventh the diameter of our Moon, it is not a very large satellite. Before the Cassini mission, very little was known about it and because of its small size no one expected it to be such an exciting place! During the Cassini flybys, however, many discoveries have been made.

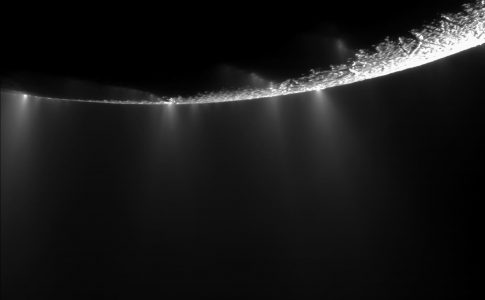

The unmanned Cassini spacecraft made a number of flybys of the moon, getting within 50km of its surface. This surface is very intensely ridged and fractured with the crust having clearly been broken and shunted around a lot. Enceladus has a small, yet significant atmosphere in comparison to most of Saturn’s moons, with Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, as the sole exception. This atmosphere is primarily water vapour, about 91%, with nitrogen, carbon dioxide and methane making up the rest. Cassini also observed active, cryovolcanic geysers, or ‘plumes’ erupting from the south pole of the moon clearly indicating that there is a layer that is completely molten, or even an ocean of salty water. These jets consist of crystallised water ice, with ammonia and assorted organic compounds being expelled into space, so something must be providing the pressure. Matter from the plumes has in fact been collected by the Cassini mission in the spacecraft’s particle detector. The particle detector was originally designed to detect particles captured in Saturn’s magnetic field, but having found the plumes, the probe flew through them to obtain samples.

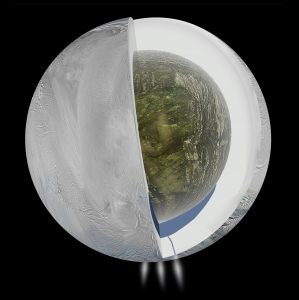

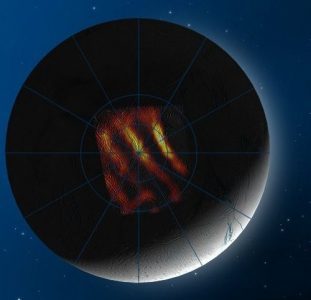

Cassini’s infrared spectrogragh also produced a map of thermal emissions from the moon’s famed ‘tiger stripes’ and found features that were at much higher temperatures than their surroundings indicating that heat must somehow be provided from an internal source. The temperature of this region are typically 85-90K (Kelvin*) with small areas as high as 157K. New evidence announced on April 3, 2014 reported the presence of liquid water buried beneath 30 to 40km of ice at the South pole. This body of water is thought to be 10km deep and may be as broad as Lake Superior, but much deeper.

As to how this water is heated enough to remain liquid, this is most likely to be due to tidal forces created by Enceladus’ orbit around Saturn, which causes the moon to deform. Friction during deformation generates heat. This is what is known as tidal heating and causes temperatures to build up below the moon’s surface. This rise in temperature melts some of the ice, creating pockets of pressurised icy liquid, mostly water but with ammonia and other impurities acting as antifreeze. This pressurised liquid escapes and expands into the plumes we see.

It is also presumed that the bottom of this body of water is in direct contact with the rocky core of the moon, this is important as pure water is not terribly exciting biologically, the water needs to interact with the underlying rock in order to dissolve minerals and chemicals and molecules which can provide useful stuff, for example, sulfur and phosphorus which are important elements to help support life. On Earth, we have hydrothermal vents where seawater can be in contact with rock and allow chemical reactions to occur so it may be that Enceladus could have similar mechanisms to enable this.

Cassini is scheduled for three more flybys of Enceladus in 2015 which also includes flying through a plume to gather more data. Cassini’s spectrograph will also be employed to gain more information about heat coming from between ice fractures in order to have more precise information about how the moon can generate heat. Now handy as Cassini is, we need to send a craft there which is tailored to answer as many of the questions this intriguing, fascinating little moon has given us.

* – For those unfamiliar with the Kelvin temperature scale, it is a heat scale largely correspondent with the Celsius temperature scale, but more scientifically useful. 0 Kelvin is also known as ‘Absolute Zero’, and represents a total absence of any heat energy. The freezing and boiling points of water, 0 degrees Celsius and 100 degrees Celsius, sit at 273.15 and 373.15 Kelvin, respectively.

This article originally appeared on TheMittani.com, written by Feiryred.