One of the doctrines that’s been most talked about lately is the Boosh Raven fleet. The Initiative and other small groups pioneered Boosh Ravens. From there, they spread around the game fast. Boosh Ravens saw extensive use in the Anime War, 9-4 skirmishing, and most notably in the Siege of Rage. The last of those then served to kick off a wave of using this doctrine to evict wormholers. There, defenders proved unprepared to defend against them.

Boosh Ravens are a powerful tool for citadel assault. In fact, they may be a little too good. I have experience fighting both with and against this fleet composition. As such, I’m going to present a point by point breakdown on what makes this doctrine so effective. I’ll also highlight some ways devs can weaken the doctrine. These won’t include nerfing the Micro-Jump Field Generator, though. The MJFG adds a significant amount of interesting gameplay. Some of these are stealing excavator drones and spearfishing. It’s worth preserving.

To do this, I will build on the concepts I first described in my article called Sphere Theory. I recommend it if you want to understand this method of evaluating fleets.

The Sniper Battleship

Ravens are not the only ship that can serve as the main DPS ship. Rokhs and Barghests have filled that role, as have other battleships. That choice doesn’t have much impact the doctrine’s ability to impact the battlefield.

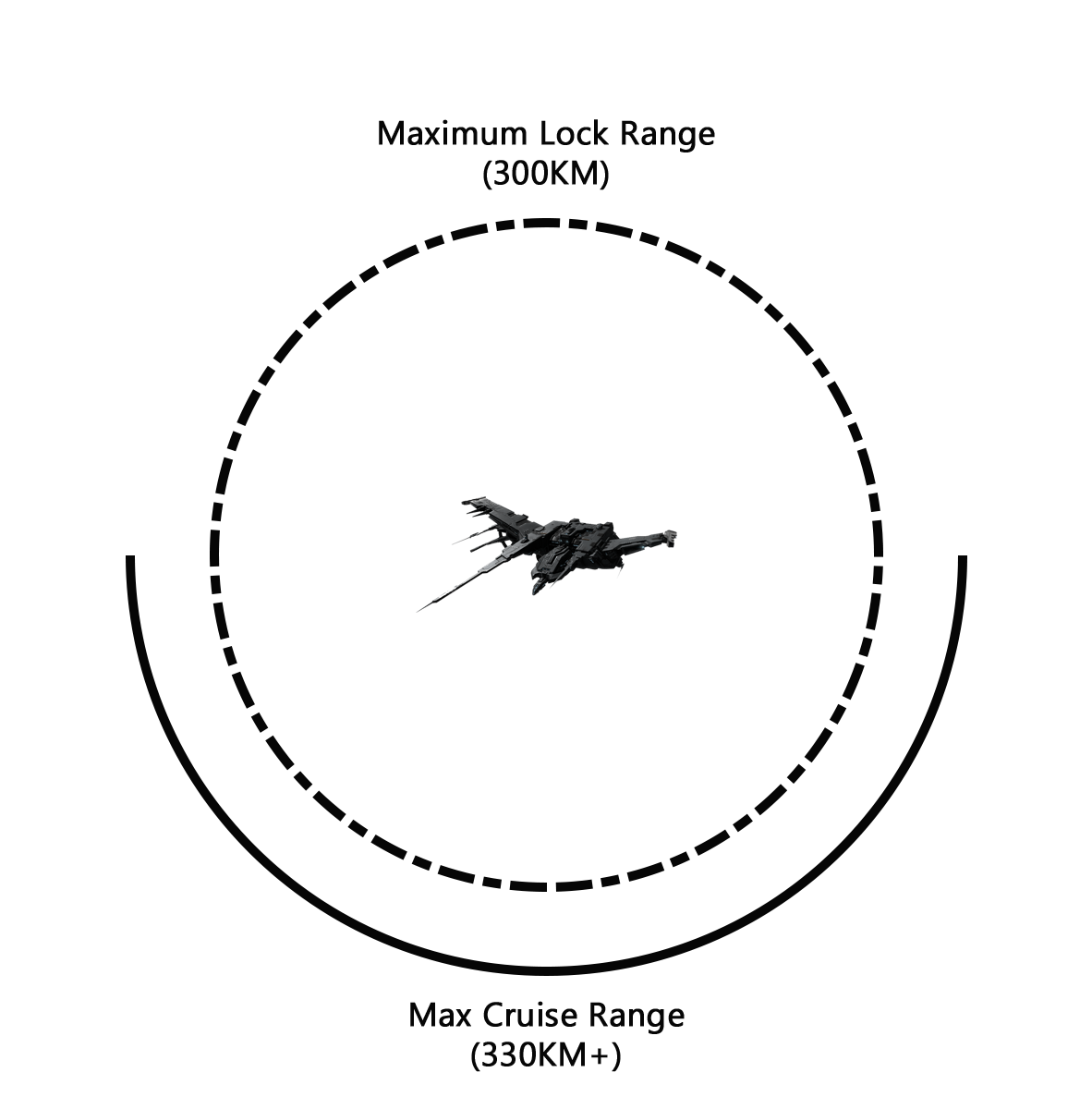

The main thing that these ships share is the ability to lock and project effective damage up to 300km. 300km is the furthest lock range of any ship which is not a Carrier or Supercarrier using an NSA. This gives the DPS core of the doctrine the greatest possible engagement envelope.

This means that there is no place on the grid that a subcap can shoot at Ravens where they cannot shoot back. Situations do exist where the Raven’s extra 30km+ lock range matters. It means opposing fleets can’t ‘outrun’ the missiles during flight. Friend-or-Foe (FoF) missiles will also select targets beyond the lock range max. In my testing, though, FoFs will not lock on to structures that are not shooting them. So this has minimal battlefield application.

This means that there is no place on the grid that a subcap can shoot at Ravens where they cannot shoot back. Situations do exist where the Raven’s extra 30km+ lock range matters. It means opposing fleets can’t ‘outrun’ the missiles during flight. Friend-or-Foe (FoF) missiles will also select targets beyond the lock range max. In my testing, though, FoFs will not lock on to structures that are not shooting them. So this has minimal battlefield application.

Another aspect that all these fits share is that they use a backup MJD in their fits. That allows the fleet to ‘starburst’ in a 100km sphere. The rapid starbust makes it difficult to defeat the doctrine in detail. Successful FC/Anchor headshots can be responded to by using it to disengage. And that even works in cases where ChemoLokis are able to kill off the Command Destroyer core. (ChemoLokis are an adaptation of the Smartbomb Proteus seen in WH explorer hunting.) This means that the fleet can re-form off-grid without having to reship all their members. From there, they can re-enter the battlefield. As a result, the doctrine must be ‘caught’ many times during a single reinforcement timer to save the objective.

Ravens are the most common ships chosen for this role. The simple reason for this is that they can do 600-900 DPS depending on the ammo used/skills of the pilot. That outstrikes pretty much any other ship at 300km. This makes them a realistic threat to capitals, especially Force Auxiliaries in Triage. It is also easy to reach the damage cap on even large structures like Keepstars.

That’s not to say that these sniper battleships are the be-all and end-all of line ships though, far from it. They have multiple weaknesses. Their DPS is somewhat limited in application vs subcaps. They also have very minimal tank. In fact, almost any mainline doctrine can outfight a Raven fleet at ~100km range. Which brings us neatly onto the next key part of the doctrine.

Micro Jump Field Generators

The Micro-Jump Field Generator (MJFG) is a mid-slot module limited to the 4 (soon to be 5) command destroyers. For the purposes of this doctrine, the Pontifex and Stork are the most utilized. This is because they are the two command destroyers with the highest EHP. That’s important, because they are priority targets for any opposing fleet. So this gives them the most chance of surviving any potential incidental damage. Triglavian ships have even better base EHP than their empire counterparts continues. So when the Triglavian command destroyer comes out, it may fill the role in armor fleets.

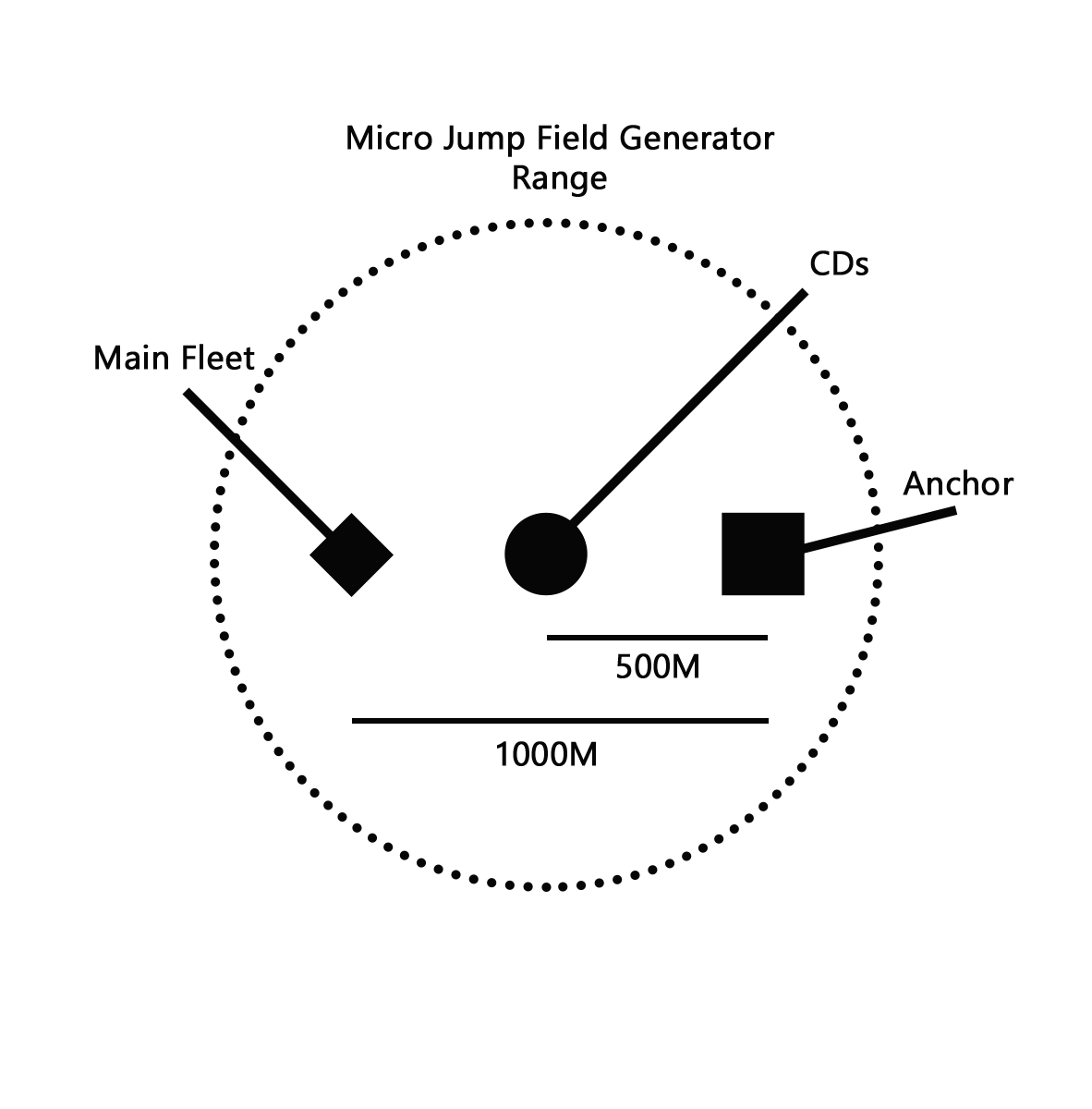

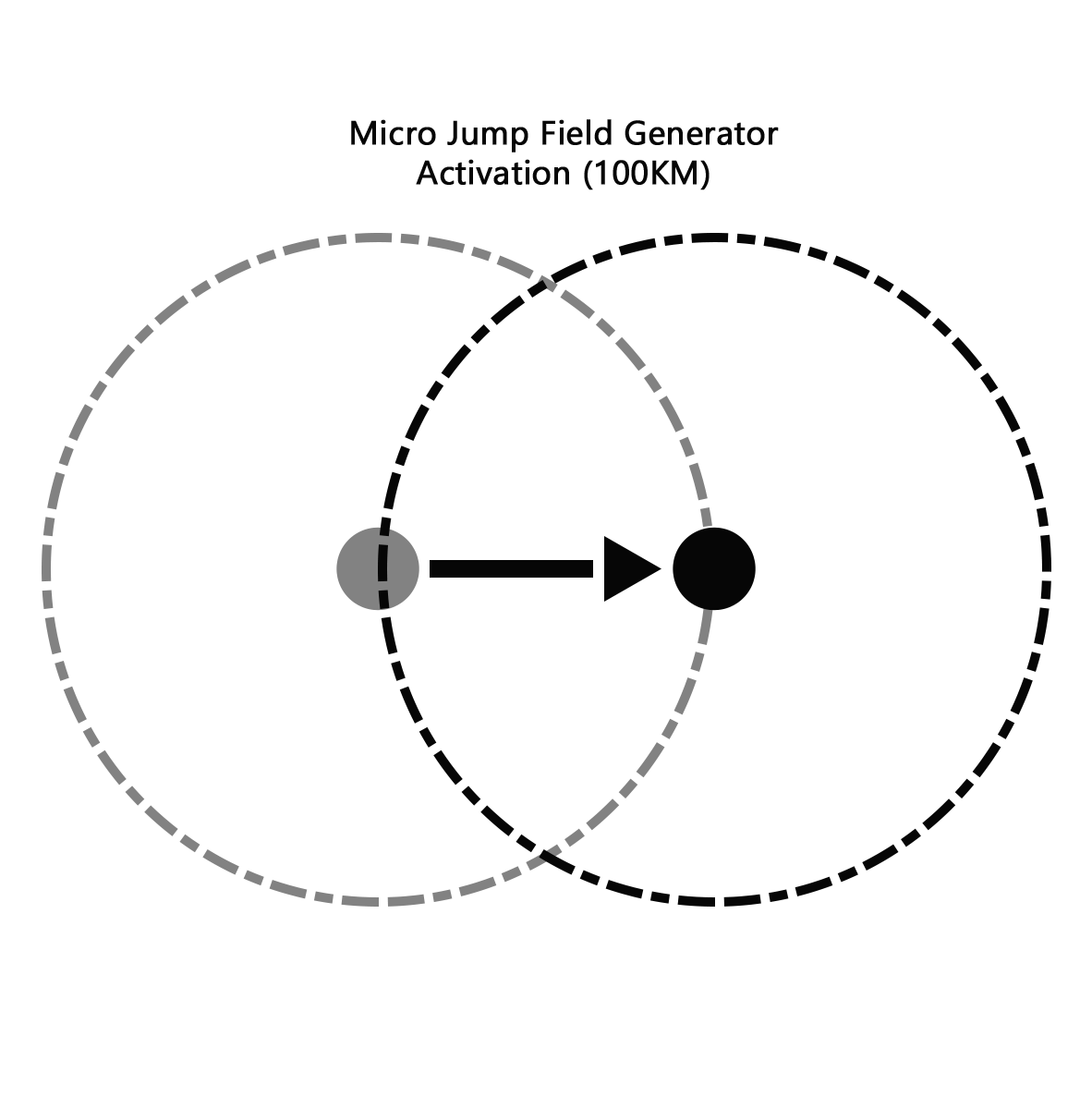

The MJFG moves command destroyers 100km in the direction they were travelling. Any sub-capitals within 6km of their model centre are moved as well. There is, however, after a brief “spool” period for the module. During this period, the Command Destroyer becomes very in-agile. To take advantage of this, ships anchor together in close form. Battleships and command destroyers use separate ranges. This lets them ensure that they are not bumped out of alignment during this process. Such a mishap would send the fleet in the wrong direction.

If operated correctly, this allows the fleet to travel as a ball, shifting their engagement envelope around the grid 100km at a time.

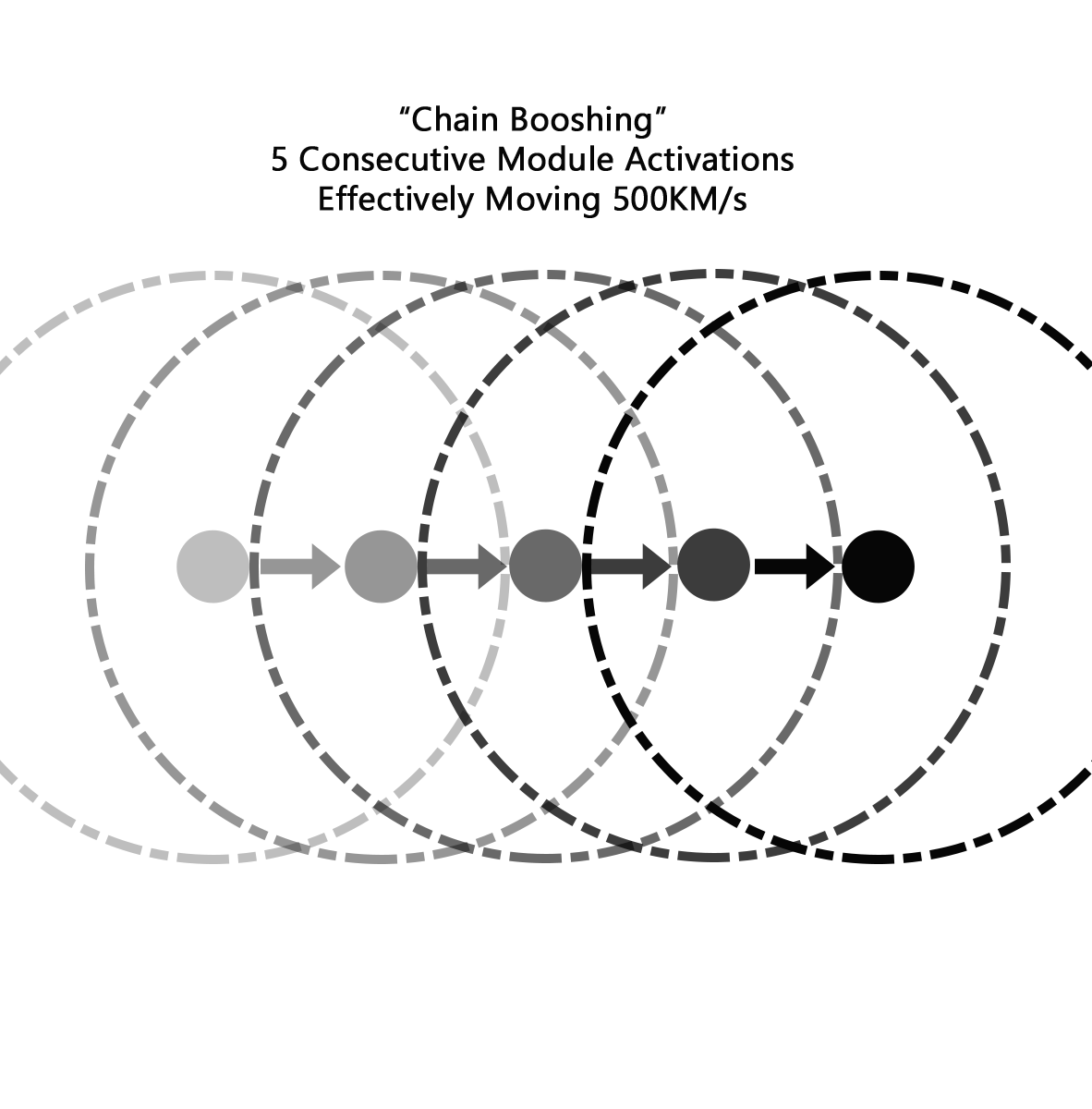

The module has both spool-up and reactivation timers, and two ‘booshes’ won’t apply to the same ships on the same tick. But that doesn’t mean the same ship can’t be booshed again on the next tick. As a result, with multiple command destroyers, this allows for relatively rapid movement, as long as formation can be maintained.

This allows the fleet to move around the grid and re-position faster than others fleets. It also comes without the normal penalties to the fleet which would be expected being applied to it. The MJDFG does not apply a signature bloom to ships it affects, break target locks, or even make weapons stop firing.

This allows the fleet to move around the grid and re-position faster than others fleets. It also comes without the normal penalties to the fleet which would be expected being applied to it. The MJDFG does not apply a signature bloom to ships it affects, break target locks, or even make weapons stop firing.

Over time, FCs have learnt how to better execute turns and keep themselves well out of hostile ranges with this doctrine. Also, the addition of the Monitor to the game made headshotting the anchor (and thereby disrupting this formation) significantly more difficult. However, that maneuverability is only as important as the ability to leverage it. With that in mind, let’s explore just how the battlefield has changed recently in order to get an idea of why Sniper Battleships That Can Run Away is an effective way to wage structure warfare.

An Expanded Battlefield – More Problems With Citadels

I realise that for some in the audience it now must seem somewhat antiquated to consider fighting over PoSes, given that there is little reason to do so any more. Still, I’m going to start with them in order to show what Citadels changed about how attacking structures works;

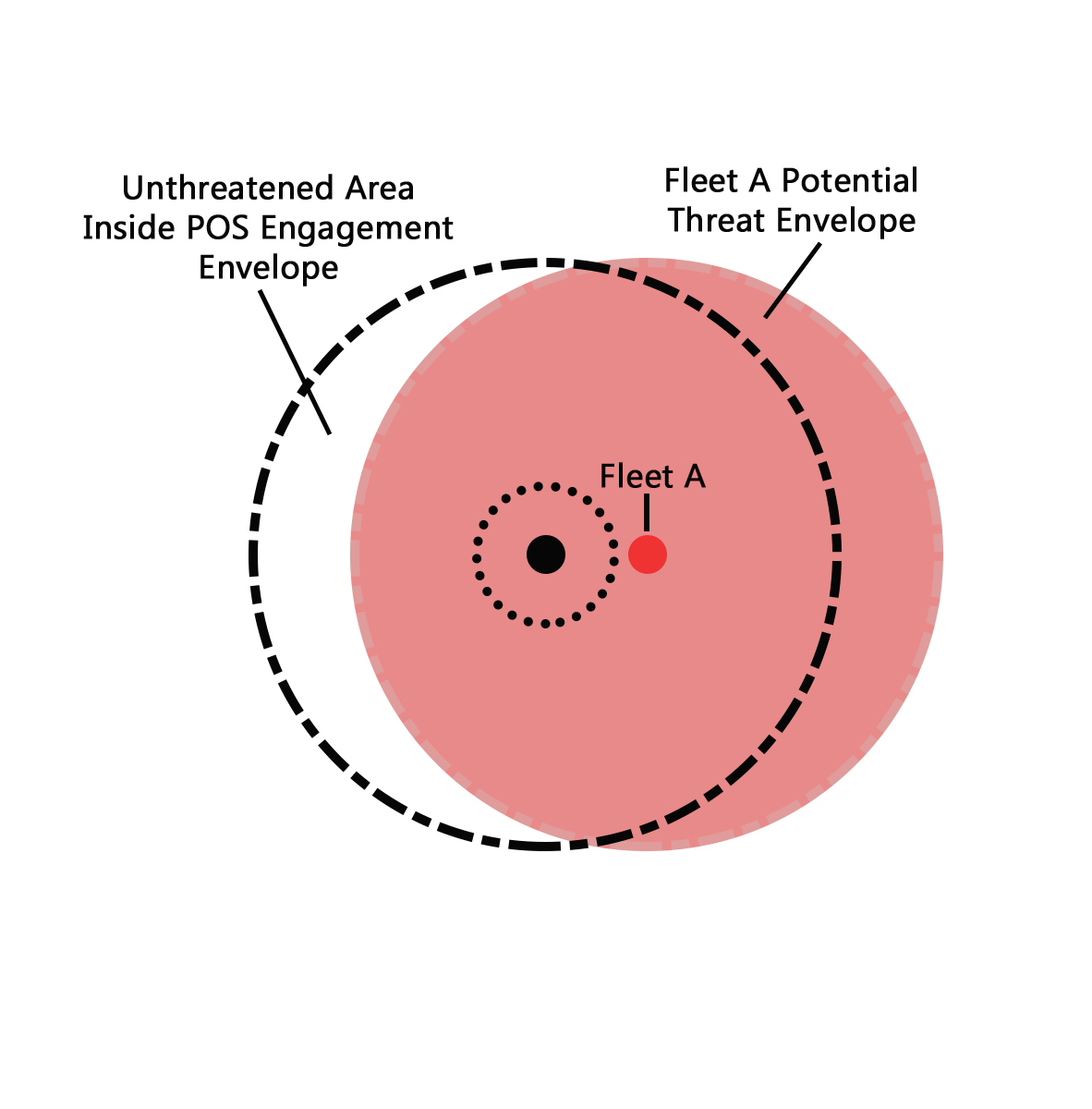

PoSes, or Player-Owned Starbases, are simple, relatively small objects, with a model a negligible few hundred metres in width. That allows us to neatly simplify it to a point for our purposes here. This means that there’s only a 300km-radius sphere in which ships can lock the PoS and shoot it, with a small chunk of space in the centre from which fleets cannot engage from thanks to the forcefield.

A single fleet, massed in a single location, can lock a significant portion of the space in which a fleet could be positioned and still engage the structure. That leaves only a small area uncovered by that fleet’s potential threat envelope due to the offsetting forced by the forcefield.

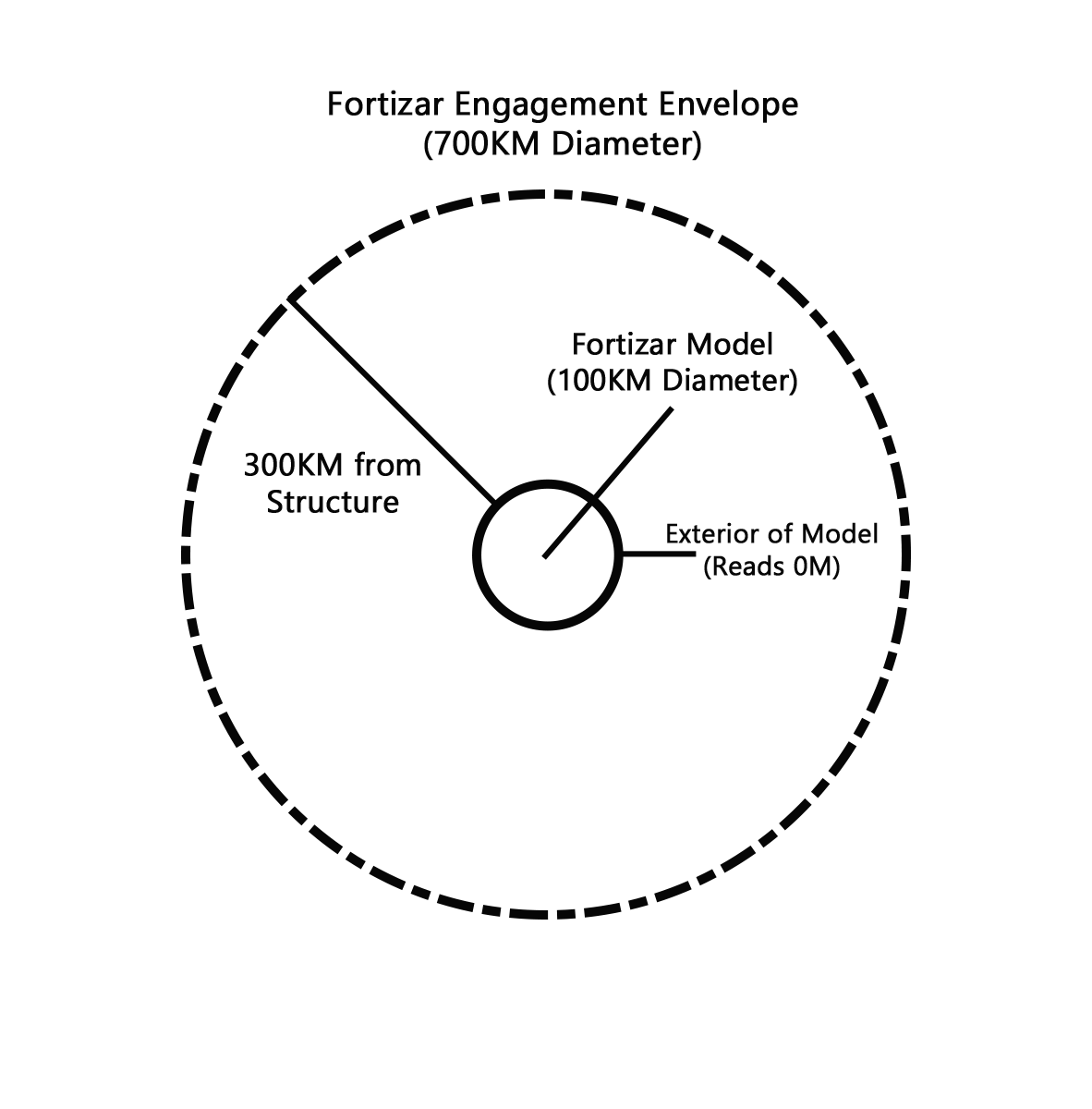

Citadels, on the other hand are much larger models. That matters, because EVE handles ranges via edge-to-edge measurement instead of centre-to-centre. So this massively expands the volume of space from within which the structure can be shot.

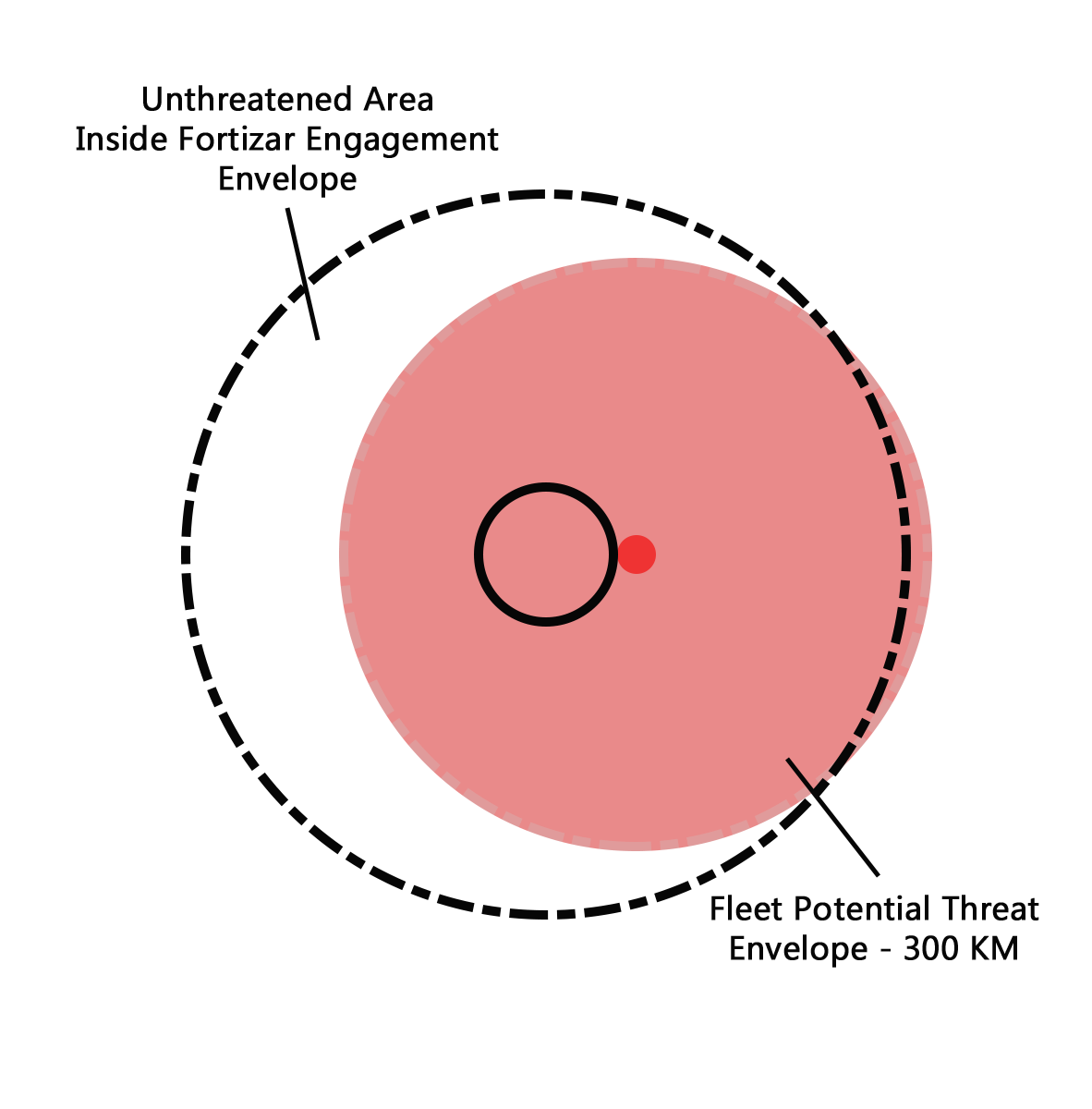

As a consequence, the percentage of volume within which a fleet can have a potential threat envelope drastically decreases, taking it from 85.04% (assuming Fleet is 30km away from PoS stick) to 62.97% on a Fortizar. The effect is even more pronounced with regards to Keepstars, where a single fleet’s threat envelope only covers a maximum of 42.18% of the battlefield, half of what was possible on a PoS based battlefield.

This makes maneuverability on grid a significantly stronger asset, as there is more space to run away from an enemy fleet, whilst still being able to continue engaging the structure.

Counter-Counter Measures

The final thing that makes the Boosh Raven doctrine tick is its slick array of support ships. These serve to protect the fleet from various AoE or otherwise close range threats that would otherwise pose a huge risk to the lightly tanked ships, or the Command Destroyers which facilitate their mobility. Some of the options I’ve noted include;

- ECM Bursting Scorpions – Used to counteract tackle attempting to scram ships down

- Defender Launchers – Used to counter bombs

- Utility Smartbombs – Used to kill alpha-strike interceptor fleets warped in at 0

- Over-Massed Exequrors – Used to neuter Keepstar Doomsdays (as they target the ships with the biggest mass)

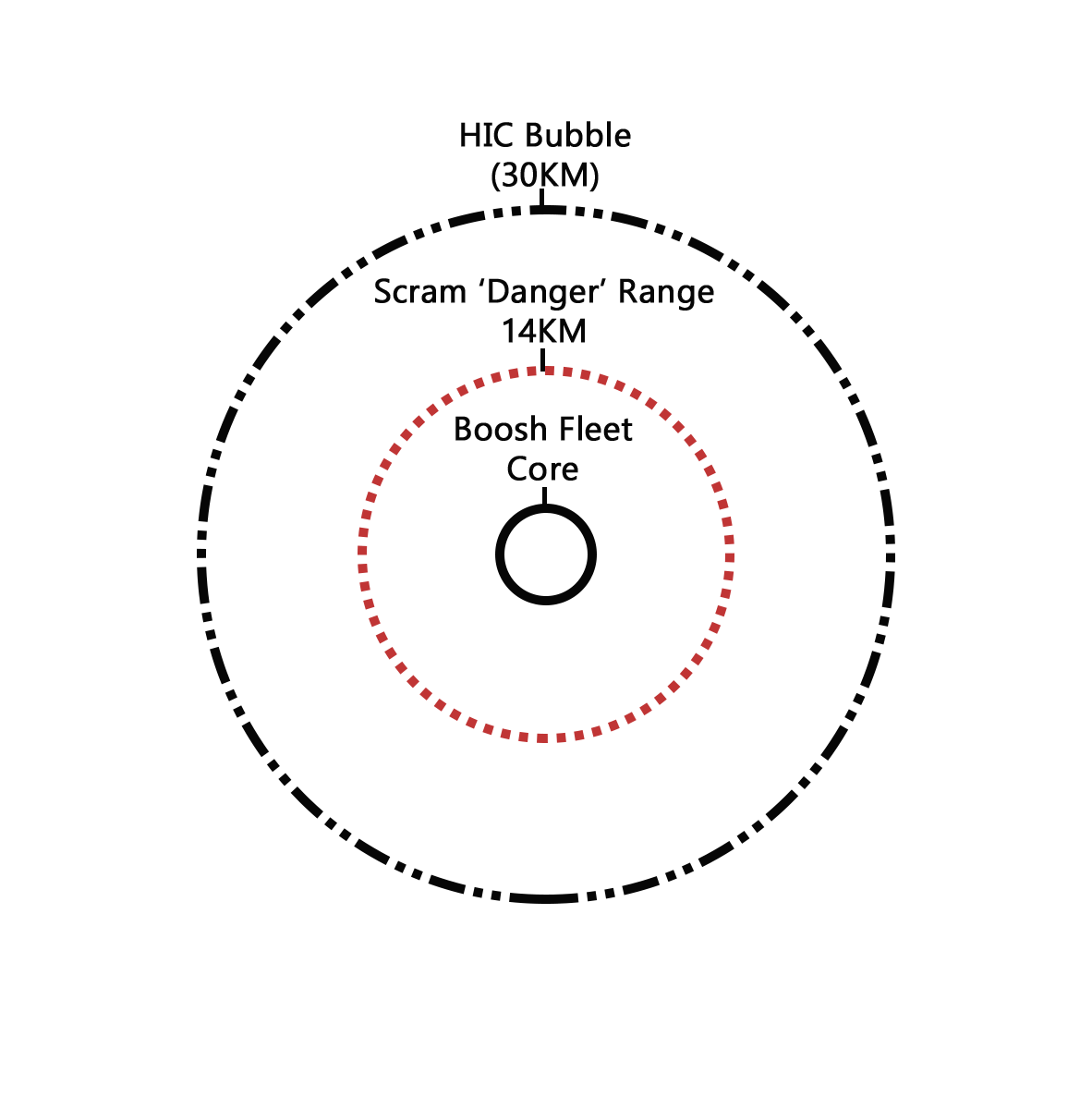

However the specific ship which has the most potent defensive role is the Heavy Interdictor. These typically have their bubble operational for most of the fleet’s duration. This provides a mobile “drag bubble” effect that prevents hostiles from warping close to the core of the fleet.

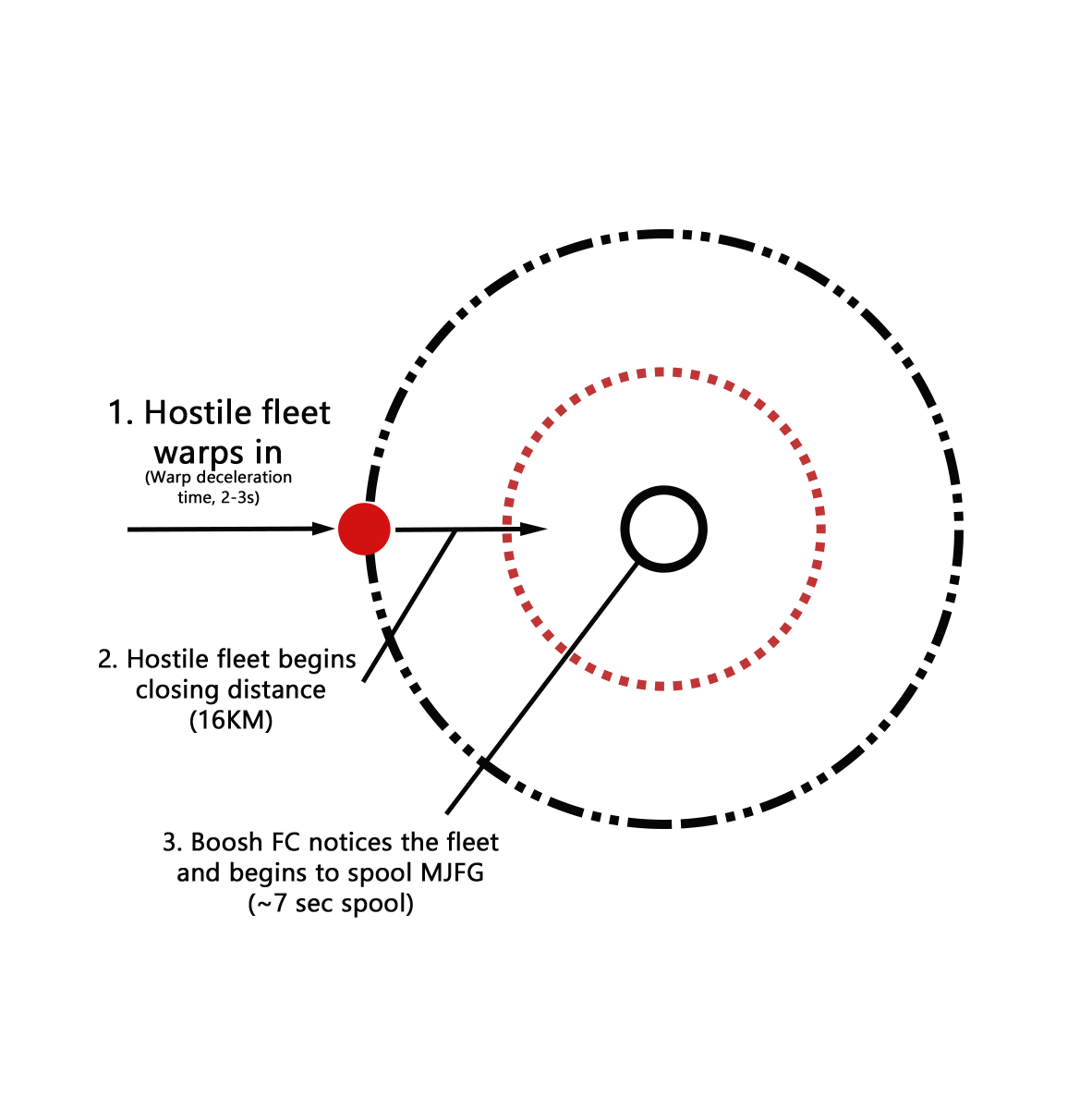

With that in place, any fleet attempting to warp on top of a pausing Raven fleet has an incredibly difficult time closing distance. That makes it hard to land the scrams needed to lock a significant number of ships in place. They may have only 3-5 seconds to do so after the pause given by warp deceleration.

Failing to land scrams leaves the close range fleet in the lurch. The boosh fleet will now be 100-200km away from them, and able to shoot at them with impunity as they attempt to rally. As a result, close range fleets are an incredibly ineffective counter to the doctrine, even when on paper they should be capable of easily having the upper hand.

What Does This All Mean?

First off, it means that Boosh Ravens are not the symptom of one module (MJFGs) being broken. The doctrine itself relies on the synergistic application of many different techniques to create a very specialised and effective fleet. That fleet can take advantage of changing battlefield conditions, and gives groups a relatively risk-light way to siege their opponents’ structures.

I do hope, however, that this has served to illustrate some of the issues with the doctrine as it pertains to wider game health. The fact that the doctrine has next to no effective subcapital counters makes it especially potent in the mass-limited world of wormholes. Carriers, long-range dreadnoughts, and titans are the only effective counters. They allow for the projection of fleet level DPS at extreme ranges in relatively small numbers. That, in turn, allows them to be spaced out on the grid in order to present multiple overlapping threat envelopes.

My suggestions as to how to open up more counterplay to this doctrine without impacting the other use cases of MJFGs would be the following;

Disallow the MJFG-ing of HiCs with their bubble up.

This would allow close range fleets to attempt to warp in on the Ravens. It creates more potential for them to be caught out and pinned down if they sit still for too long. Currently, this is not a threat they have to consider. There is the potential for fleets to simply replace HiCs with Interdictors dropping repeated bubbles, but I am unsure how efficient that would be. As well, I don’t wish to mess with the current mechanics of MJFGing bubbles away from ships that are tackled (although I’m personally against that being possible).

Make the MJDFG give an AoE Signature Radius penalty during use

This would give Boosh Ravens a meaningful penalty when chain booshing, and would prevent using it to ‘Drift’ around a grid in such a way that they never spend enough time in any one capitals’ range to be locked. Distributed LR dreads and titans could then serve as a more meaningful counter in pitched battles.

These changes wouldn’t remove the Boosh Raven fleet from the meta, but would give it significantly more weaknesses. Those weaknesses would make it more engagable with a wider range of fleet options. I think it’s important (and to some extent inevitable) to have a good, somewhat safe structure bashing doctrine in the game in order to facilitate the creation of timers. However, said doctrines should be beatable with enough preparation and forethought, and I hope I have demonstrated why that is currently not the case in the meta.